Turkish Traditional Archery – Part 1Turkish Traditional Archery

Part 1: History, Disciplines, Institutions, Mystic Aspects

Turkish traditional archery’s roots go back to the first millenium B.C. to Scythian, Hun and other early Asian archery tradition. The horseback archers of Central Asian steppes have used very similar archery tackle and fighting strategies throughout entire history and the nomadic life style avoids making a clear, distinctive categorisation of the tribes and nations. These nations have lived on the same geography, shared many values and influenced each other’s religion, language, tradition and undoubtly genetic code. In the complex ethnic genetic pool of Central Asia the historians try to find their ways in chasing different linguistic tracks which however is not a reliable argument neither. There is a common culture consisting of social life, religious beliefs, accomodation, art as well as hunting and fighting techniques. Numerous civilizations appeared and disappeared from the history scene throughout centuries and left this common culture and archery school. No need to tell about the fact that history has been used (or misused) by various political foci and the truth was sometimes distorted by historians. Although the ethnic continuity is questionnable, the Asian archery tradition passed to Avars, Magyars, Mongols, Seljuk and Ottoman Turks with a gradual development in the tackle. Compromising with the official histiography, the word “Turk” was first used in Chinese sources in early 6th century for a Turkish nation called “Blue Turk Empire” (Kökturks). Recently a new term, “Turkic” appeared to describe Turk-related tribes or pieces of the Central Asian culture. Although it’s not easy to follow the specific tracks back to Blue Turks, Ottoman archery is very well documented. The high level it reached, especially in flight shooting is the reason that western world knows and admires the Turkish archery. Turkish traditional archery can be examined in three time intervals: 1- Archery of pre-Islamic Turkish and Turkic tribes 2- Archery of Turks of Early Islamic era 3- Turkish Archery in the Islamic time frame Archery of pre-Islamic Turkish and Turkic tribes Although the pre-Islamic Turkish archery has not been very well documented, the archaeological excavations made by the former USSR scientists illuminated many dark spots. Additional information sources are old pictures, reliefs and sculptures. According to Gumilöv[1] the sculptures in the collection of Ermitaj Museum describes the typical Turkish mounted archers. The tails of the horses are knotted -a tradition that reachs to Ottomans- the styles of the clothing and saddles indicate the use of bow and arrow on horseback. For the early-Islamic phase of Turkish archery, there are 9th century Arabic texts in which the archery skills of partially Islamized Turks are well described[2]. The skills of horseback archers, especially their ability to hit moving targets from on horseback are explained in detail. The most important source available that includes many details about this stage is “The Book of Dede Korkut”[3]. This book that is sometimes called as “The Turkish Ilyada” contains epic stories, probably written in 12th century but has its roots in hundreds of years before. Other than the linguistic character of the text, social life and beliefs exhibited in the stories indicate a “passing phase” rather than an established Islamic life. Many authors agree that the Islamic motifs have been put later into the stories. In The Book of Dede Korkut it’s possible to find indicators about how important bow and arrow have been in the nomadic life of Turks. As an example of shamanist-ceremonial use of bow and arrow it is remarkable that the groome was releasing an arrow and building his first night’s yurt to the spot where the arrow landed. You’ll even come across to indicators of recreational aspects of archery! In a wedding scene the groome and his friends were competing in hitting a small target with bow and arrow, the target being a ring of the groome. Another point which should be noted is the importance of women as warriors in the pre-Islamic nomadic life as it’s also told in Marco Polo’s travel reports[4]. In the Book of Dede Korkut this truth is expressed in one of the stories: A character named Bamsi Beyrek lists the requirements he was looking for at the girl he’d be married. Besides many other martial skills, he expected her to be capable of drawing two bows at once. There are often referrals to the “heavy bows” of the heros in order to appreciate their physical strength and to honour them. Adopting Islam has been a result of the 300 years of commercial, social, religious and cultural interactions between the Islamic armies and the north-neighbouring Turks in the region called “Maveraünnehir”. This interacton ended up with a change of religion and alphabet of Turks[5]. Turks must have noticed and admired that their new religion gives importance to archery, a martial art that already had great importance in their lifestyle. Additional to a verse in Quran there are fourty Hadis in which people are encouraged to practise archery[6]. Seljuks have opened the doors of Anatolia to Turks. It was the skill of Seljuk mounted archers that brought them to their destiny. The historians of that era described them as an highly effective, moving force with the long-ranged weaponry. They were hesitating to “impact” the enemy and to get into close quarter fighting. What they preferred was a lightning-fast “attack and retreat” strategy based on horseback archery skills. Their shorter recurved bows were easier to handle on horseback and gave the warriors great flexibility.

Picture 1: Another document from Seljuks is a coin produced during Sultan Rukneddin’s (Kılıçarslan IV) reign. Please note the Turkish and Islamic name of the Sultan: another sign for the “passing phase”. Here you see a short recurve and two more arrows in the string hand, the latter indicates the use of thumb release by Seljuk archers. It’s documented that each warrior was carrying about 100 arrows in the quiver, in the bowcase and even in the boots. The consequences was reported in a battle against I. Crusade army: The knights had to stand a 3 hours of uninterrupted arrow attack[7]. The best documented stage of Turkish archery however is the Ottoman Archery. This empire that was supposedly founded in 1299 by an unsignificant tribal leader, Osman Bey, has ended the Roman Empire and ruled on three continents. In Ottomans, archery was practised with its various disciplines at an institutional level. The prevails of this institutionalization were the “Okmeidan” (literally means “Place of Arrow”) and the “tekke”[8] where archery as a sport has been taught and practised since the beginning of 15th century. This is supposed to be the first sportive archery in the history and started a hundred year before the foundation of “The Guild of Saint George” with the order of Henry VIII. The first Okmeidan was established in Edirne, the second capital city of the empire prior to Istanbul. It’s followed by numerous others and the most famous one was the Istanbul Okmeidan, founded by Sultan Mehmed II, just after he conquered the city. The property was bought by the Sultan himself from the owners in a price that was twice of its cost. The Sultan gifted this place to archers, made them build the “tekye-i rumât” (lit. “tekke of shooters”) on it. The expanses of this archery resort was being reimbursed by foundations. The tekke was respected as a holy place and protected by law. It’s worth to note that systematic para-martial archery training was being given long before the firearms gained prominance on the battle field. Flight shooting, the less war-related discipline, has always been popular although its popularity increased after the development of firearms in 17th century. Among the archery disciplines the two major ones were target shooting and flight shooting. The target archery can also be subclassified into three categories: puta shooting, darb (piercing) and horseback shooting. Puta shooting was shooting arrows to specific leather targets called “puta”, from 165 to 250 m distance. Puta was a pear-shaped, flat leather pillow filled with cotton seed and sawdust. There were colored signs serving as a bull’s eye on the face and little bells were attached on the skirt to provide a sound signal of the hitting arrow.A sample in the collection of Military Museum in Istanbul reveals the puta’s size: 107 cm X 77 cm. That distance is supposed to be the optimal distance in which the archers made aimed shots at the enemy. Sometimes large baskets were used for the same purpose and were called “puta basket”. Smaller stationary and “hand-held putas” were used as well but shot from closer distances.

Picture 2:Sultan Selim I (1512-1520) pratising on a hand-held puta or “ayna” (Hünernâme, 16th cent. Library of Topkapı Palace Museum). Another variation of target archery practice was called “darb” and was based on piercing hard objects. It was a war-related practice for acquiring the skill to pierce the armour of the enemy. The armour piercing capability of the composite bow has always been discussed, especially if it comes to the plate armours of late medieval and early modern times. Euro-centric historiography has always had the tendency of highlighting the military success of English Longbow in Hundred Years Wars. The military success of the step civilizations with the composite bow has somehow been ignored while their defeats were exaggerated. However the claim that the armour piercing capability of the composite bow is weak, is only a myth. This truth was noticed first by Romans and Sassanids. When Huns invaded these two empires in the 5th century, both the Persian and the Roman armies had heavy cavalry with plate armor (clibanarius and cataphractos). Romans’ infantry had even two layered chain mail and heavy oak shields as personal protection. Both states realised that the Huns have had no problem in piercing their armours. This has been achieved by the siyah-tipped Hun’s bows[9]. And the effect of Turkish bow, the ultimate Asian composite bow, has been perhaps most fully witnessed by the Habsburgs. Field Marshal Monteccucoli in his memoirs; along with Graf Marsigli whom’s detailed report about the Otoman army in 1682, advised to the Habsburg army to be careful about the Otoman archery because the Turkish arrows were able to easily pierce Austrian Curiassiers’ plate armor[10].

Picture 4a, 4b: Samples of darb targets are on exhibition the Military Museum in İstanbul (Photograph: Z. Metin Ataş). Shooting targets from on horseback was another target discipline and mounted archery has been very popular between 14th and 17th century. The most popular application of horseback archery was the so-called “qabak game”.There were even special fields for this game. Although “qabak” is a vegetable, many other objects like cups, balls etc. were used as target. The target was put on the top of a tall column that the archer was approaching with full speed to. He was passing the column, turning back and shooting the target. Qabak game was not only a war-related practice but also an occasion for demonstrating skill and for entertainment.

Picture 5: In this miniature Murad II is shown playing Qabak game in front of foreign envoys (Hünernâme, 16th cent., Library of Topkapı Palace Museum). The other main discipline of Ottoman archery, flight shooting, has been the reason of the interest of western world in Turkish archery. Flight shooting is very far away of being a war-related discipline and is a pure sport in any means. In my opinion there have been three milestones at which the attention of western world was attracted. In 1795, a Turkish consulate in England named Mahmud Efendi have shot three flight arrows when he was hosted by the members of Toxophilite Society. The distances were carefully measured and the longest one was surprisingly found to be around 440 m which was ca. 100 m further than the maximum range ever reached with an English longbow. Besides, Mahmud Efendi told that he was not in good condition, neither was his bow and after all he was just an amateur[11]. He really meant it as it will be seen later in this article. Secondly, the book Telhis-i Resail-ü’r Rumât written by Mustafa Kani Efendi in 19th century has been translated to German by Joachim Hein and published. Dr. Paul E. Klopsteg wrote his famous book “Turkish Archery and the Composite Bow” in 1930’s that was based on this translation Telhis-i Resail-ü’r Rumât was written by Mustafa Kani bin Mehmed with the order of Sultan Mahmud II who was also an excellent archer. The book was introduced to the sultan as a handwritten text and published a few years later, in 1847 in İstanbul. This book consists of detailed information and even illustrations about archery, bowyery and arrow making. If we’d have a look at some specifications of Turkish archery which differ it from other styles and traditions, we would see a “Top 7 list: 1-The first sportive and recreational archery known in the history. Many Okmeidan were founded in the early 15th century. The first Okmeidans were founded in the early 15th century in Edirne and Bursa. The Okmeidan of Istanbul was a foundation of Sultan (Fatih) Mehmed II in 1453 just after the city was conquered.

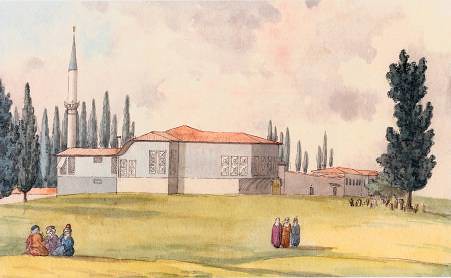

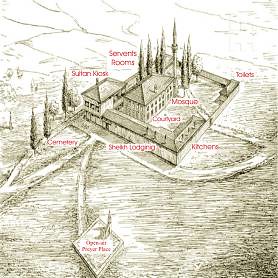

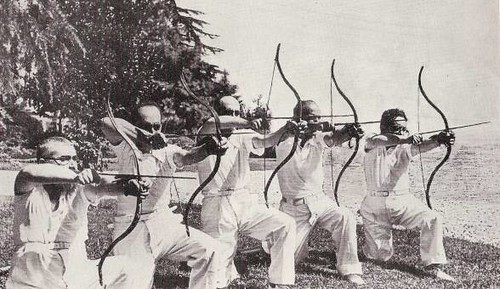

Picture 6: Carl Gustav Löwenhilm was on duty in İstanbul as an envoy in early 1820’s. This is an illustration he made. 2- The institutions called “tekke” served as a place where systematic archery education has been provided. The acceptence and graduation of the student was being conducted by rules under a ceremonial format. “Tekke” litarally means the institution where dervishes live and are educated according to sufist (Islam mysticism) knowledge. Another meaning is the place/institution where sports like wrestling or archery are being taught and trained. They were very similar to today’s sportsclubs.

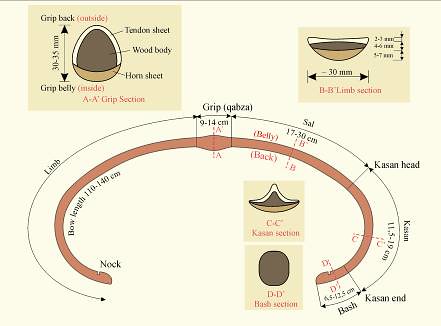

Picture 7: This picture represents the tekke as it was illustrated by Halim Baki Kunter in 1938 according to the descriptions in the old scripts (Eski Türk Sporları Üzerine Araştırmalar, 1938). Kunter was one of the most important archery researchers of republic era. The archaelogical excavation started last year resulted in finding the base of all these buildings except that of the toilettes. It confirms the results of Kunter’s work. The beginning and end of the basic archery education used to be celebrated and declared with ceremonies. The acceptence of the student was formalized with the “Little Qabza Taking Ceremony” and then graduation was formalized with the “Big Qabza Taking Ceremony”[12]. The declaration of the student’s proficiency was possible only when he could shoot a pishrev arrow[13] to 900 gez (594 m) or an azmayish arrow[14] to 800 gez (528 m). This particular shot must have been witnessed by a minimum of 4 persons, two being at the shooting spot and two at the spot the arrow landed. After then the archer was recorded to the Tekke’s Registration Book and accepted to be proficient. One of these books remains until today. In the Big Qabza Taking Ceremony, the “master” was dropping a bow(-grip) into the hands of the brand-new kemankeş[15] (pronounced cam-un-cash), symbolising the transfer of archery knowledge and tradition from one generation to the next one. 3- There were moral and mystic aspects of the education. Okmeidan and tekke were accepted to be holy places and were highly respected. The Islamic personal cleaning ritual called “abdest” which is a must prior to daily praying was performed before entering the Okmeidan as if this place was a temple. Although there was obvious discrimination among the social layers of Ottoman Empire, in Okmeidan all archers were accepted to be equilant like in any temple. Even vezeers and sultans were competing under the same circumstances and rules. Another example for the mystic aspects of the education and application was the “Ya Hakk!” shouting of flight shooters which means “Hey God!”. This seems to be similar to the so-called “kiai” in Japanese martial arts and it makes sense to believe that they both have the same purpose. The interesting symbolism in bow morphology is another point in the archery-related mysticism. The upper limb was symbolising the “good” or “holy” while the lower limb stands for “evil”. The grip –qabza– was accepted to bind these two polar tendencies of the universe and of the man himself. The middle of the grip where a small piece of ivory or bone plate (chelik) is inserted was the symbol of the so-called “vahdet-i vücûd”, a sufist term meaning the common identity of all universe and creatures; a projection of God. The symbolic importance of qabza makes the bow a ceremony object whereupon in the “Big Qabza Taking Ceremony” it was also symbolising the transfer of the knowledge to the next generation. The graduation of the student was declared and celebrated by giving a bow to the hands of the new kemankeş. Because of this symbolic relation all the archers used to start and finish their daily practice with the ceremonial kissing of their bowgrips. 4- Turks developed the “ultimate bow” of Central Asian school. Otoman bows are reflex and recurved composite bows like the other bows of Central Asian origin. Made of wood (mainly of acer species), sinew, horn and glue this bow is the shortest one among its relatives and is measured only 41 to 44 inches. With this length it can only be compared with the Korean bow. Its efficiency is high with both heavy and light arrows[16] which gives the Otoman flight bow the greatest cast ever known. Making such a bow requires high skill and patience. Because of the long time required for the organic materials to dry it took 1 to 3 years to make a bow.

Picture 8: The profile and the cross-sections of the Turkish bow (Courtesy of Dr. Mustafa Kaçar). 5- Pure sportive disciplines like flight shooting did exist and was performed long before the firearms gained prominance and made bow and arrow become sports tackle. The archery-related civil institutions like Okmeidan and tekke were established in the beginning of 15th century. Other than the training facilities tekke used to offer many social opportunities like dormitory, food court, library and meeting room. With these opportunities it had an identity similar to that of a modern sportsclub. Flight archery which is the less war-related discipline has always been very popular while bow and arrow were stil in use on battlefields. “Kemankeş” or graduated archers used to train hard and regularly like the elite professional athletes of modern times. It’s known that the best ones have been reimbursed or sponsored by the Palace. 6- Distances of over 800 m have been reached in flight archery. The flight records are very well-documented. According to Islamic rules the record was only valid when the shot had been wittnessed by a minimum of four persons. Each shooting range or “menzil” was indicated by two stones, one “foot stone” erected at the spot where the archer stands and a “main stone” for indicating the direction of the shot. In any attempt these witnesses who were employees of the Okmeidan had to be present. The distances achieved were not only recorded to Tekke’s Registration Book but monumental stones were also erected for the remembrance and declaration of them.

Box: Some 800+ m shots achieved by Turkish kemankeş. 7- Monumental Stones, each being a documentation and a piece of art have been erected as the remembrance and declaration of these records. The monumental stones were called menzil stones (pronounced. men-zeel). Each of these stones had a carved poetic text which contained the archer’s name, the distance achieved and the date of the record. The date was recorded in a specific manner by using “ebced”[17]. Therefore these texts have been exceptional examples of Turkish caligraphy and poetry.

Picture 9:The stone for a record shot of Sultan Mahmud II. The photograph was taken in 19th century (Courtesy of Prof. Dr. Atilla Bir and Dr. Mustafa Kaçar).

Picture 10: This is a picture of the menzil Stone of Beşir Aga, erected for the remembrance of his 630 m shot. What makes this photograph more important is that the person on the right is Dr. Paul Ernest Klopsteg at his visit to Istanbul in 1930 (Courtesy of Prof. Dr. Atilla Bir and Dr. Mustafa Kaçar).

Picture 11: This is the stone of the brilliant record of Iskender the “Tozkoparan”. The distance is 846 m and the year 1550 (Courtesy of Mr. Şinasi Acar). Unfortunately Turkish archery tradition has somehow come to an end. It probably started with the social, cultural and financial recession of the Ottoman Empire wihin the last 200 years. In 1914 the Empire got into the I. World War and the army converted the Okmeidan to a military base although any kind of invasion had always been forbidden by sultan’s orders for centuries. In 1925 all the sufist activity was stoped by law. All the tekkes including the ones with the sportsclub character have been closed. Ataturk, the founder of the new Turkish republic engaged a few man descending from kemankeş families to re-establish the modern Turkish archery. Okspor, the first archery club of Republic era has been founded in 1937 but closed in 1939, just one year after the death of Ataturk. Modern Turkish archery that is based on FITA regulations and modern tackle was established in 1950’s. This school of archery came up to these days.

Picture 12: One of the rare photographs showing the founders of Okspor. A very interesting point is that this pic is indicating a passing phase of rapidly modernising Turkey. The traditional archery tackle is combined with western clothing (H.B. Kunter, Eski Türk Sporları, 1938). In the recent years our traditional archery started to breath again. The re-birth of the Turkish traditional archery has started with the personal attempts of a few men. Thanks to the old treatises and limited number of enhusiasts around the world, the ancient technique and tackle have been recovered within a short time. Nowadays the number of enhusiasts and practitioners increase rapidly.It won’t be a surprise to see Turkish archers in the near future with their composite bows and thumbrings, competing in traditional archery events. [1] L.N. Gumilöv, Eski Türkler, 1999. [2] El Cahiz, Hilafet Ordusunun Menkıbeleri ve Türklerin Faziletleri (çev. Ruşen Şeşen), 1967. [3] A. Schmiede, Kitab-ı Dede Korkut Destanlarının DresdenNüshası, 2000. [4] K. Koppedrayer, Kay’s Thumbring Book, 2002. [5] S.J. Shaw, Osmanlı İmparatorluğu ve Modern Türkiye, 1. Cilt, 1994 [6] Ü. Yücel, Türk Okçuluğu, 1999. [7] C.W.C. Owen, Ok, Balta ve Mancınık Ortaçağda Savaş Sanatı 378-1515, 2002. [8] The original spelling of the word is “tekye” whereas it’s changed within centuries and being used as “tekke” in today’s Turkish. [9] Priscus, Historici Graeci Minores (ed. L. Dinorf), 1870. [10] Raimondo Montecuccoli, Memorie della guerra, 1702; Graf Marsigli, Stato militare dell ‘Imperio Ottomanno, 1732. [11]P.E. Klopsteg, Turkish Archery and the Composite Bow, 1947, 2nd ed. [12] Qabza means “grip”. [13] pishrev arrow: a flight arrow with barelled shaft, ivory bullet-like point and short, high-profile fletching. [14] azmayish arrow: a flight arrow with barelled shaft, metal bullet-like point and longer, low-profile fletching. [15] kemankeş, pronounced “cam-un-cash” , was used for “archer” and literally means “the bowdrawer”; a vocable with Persian origin. [16] The bow stores some amount of energy when drawn. The efficiency is up to the proportion of energy that is transfered to the arrow when it’s released. Wooden selfbows’ efficiencies go up with the increasing weight of the arrow.The composite bows however transfer more energy to lighter arrows. For the non-selective energy transferring capability of Turkish composite bows please look at Mr. Adam Karpowicz’s article at http://www.atarn.org/islamic/Performance/Performance_of_Turkish_bows.htm [17] Ebced: Each Arabic letter has a numeric correspondent which enabled the poets to date events with the poems they wrote.Even official historians in Eastern cultures used this method to record important historical events i.e wars, military victories, birth of princes, etc.  |